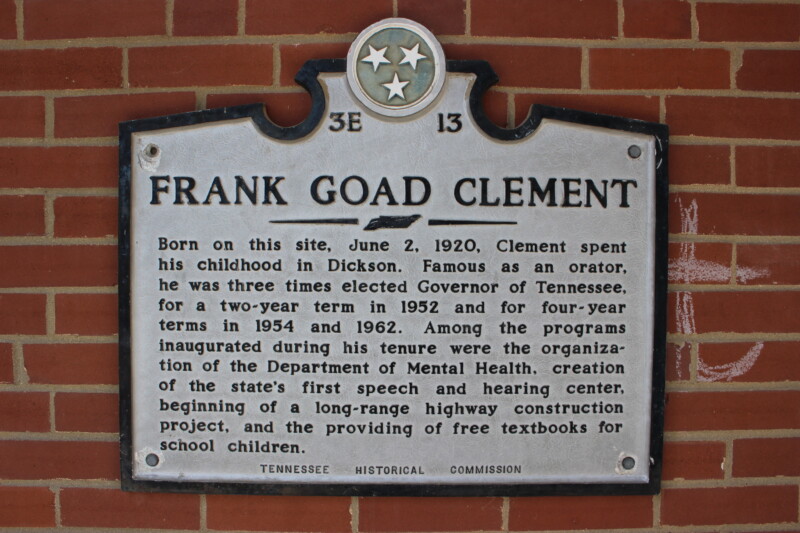

History is the story of ordinary people who have done extraordinary things. What sets many of these people apart is a gift they have been given that they are able to focus in a way to make a difference. Frank Goad Clement’s gift was oration. He could move people with the fiery power of his words. He used this gift to become one of the state’s longest running governors, and one that made a significant contribution to the modernization of the state.

Clement was born on June 2, 1920 in a room in the Hotel Halbrook in Dickson, Tennessee, a railroad hotel that his mother, Maybelle Goad Clement, managed. His father, Robert Samuel Clement, was a lawyer and local politician. He grew up playing in the halls of the hotel, where they lived in the manager’s apartment, and listening to the stories of the traveling salesmen who came through, according to a video about his history on the Clement Railroad Hotel Museum’s website. The museum is housed in the old hotel.

There are several stories about when Clement decided he wanted to become the governor of Tennessee. One says he was ten, another says he was 16, but both say that he became interested in public speaking when he was quite young and took lessons in it from his favorite Aunt Dockie Weems. He would practice with his cousin, Jimmy Weems, nights and weekends, and in high school they became the team to beat in public speaking competitions, which was then called rhetoric.

After high school, he went on to college at Cumberland University, where he was in the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity. He received a law degree from Vanderbilt University in 1942. He worked as an FBI agent for a year working on cases dealing with espionage and national security, did a stint in the Army during World War II, and then he went on to become the legal counsel for the Tennessee Railroad and Utilities Commission.

In 1948, he was an alternate delegate for the Democratic National Convention. Perhaps that is what led him to make that envisioned run for governor in 1952. He was up against veteran Democrat Gordon Browning, who referred to him as a “pipsqueak”, and saw him as no competition. But Browning was wrong. Clement traveled to all 95 counties in Tennessee and used his sermon-like speeches with many biblical references to make himself memorable to the people in even the most rural parts of the state, some of whom still remember what he said. He won the Democratic nomination 302,487 to 245,156. Then went on to beat his Republican challenger in the general election.

During Clement’s first term in office as the 41st governor of Tennessee, he floated a bond issue ensuring all students in elementary, middle and high schools who were in public education would receive free books. Previous to that, students had to pay for their own books after the third grade, and those who could not pay either had to look over the shoulders of those who could pay, or drop out of school.

He was instrumental in creating the state’s first long range highway construction plan, he created the first state department of mental health, began the shift from an agrarian economy to one of industry and manufacturing, he helped found the first school for the hearing and speech impaired, and he stood up against those who wanted public schools to remain segregated in the state. He brought out the National Guard to make sure all students were safe at Clinton High School, the first school to integrate in the South in 1956.

Clement was looking towards national office when he made the keynote address at the 1956 Democratic National Convention. While many of his fellow party members liked his 45-minute speech, the national news media crucified him. A “Time” magazine columnist named Lance Morrow dubbed it “a symphony of rhetorical excess”, and others were equally critical. His folksy, back-woods preacher style didn’t play nationally and any hopes for national office were crushed.

With changes to the term limits for the governor which would not allow him to two terms in a row, he went back to his law practice for four years and then ran again in 1963. He was once again elected. Described as tall, stately, and handsome, his personality could fill the room, but there was hushed gossip in the halls that he had developed a dependence on alcohol that some say had an effect on his performance during the last years of his last term. After his last term as governor was completed, his wife, who never really enjoyed being a political wife, filed for divorce. It was said it was the alcohol.

On November 4, 1969, at the age of 49, Clement died in an automobile accident on Franklin Road when things seemed to be turning around. He and his wife were working things out, and he had made it known that he was going to run for governor again.

Just a few days earlier he had told a friend that he wanted to have “Amazing Grace” sung at his funeral one day, but that he had no burial plot and felt like he could live forever. He left behind three sons, two of whom are living, former United States Representative Bob Clement and Judge Frank Clement, Jr.

It was Bob Clement who was instrumental in the creation of the Clement Railroad Hotel Museum as an ode to his father’s accomplishments. It tells the story of a man who flamed brightly, and then died perhaps before his time. Or maybe, like many before him who accomplished much early in life, he used up his gift and sadly it was his time to go.

As Earnestine Adams, a Clement Railroad Hotel Museum board member, says in the video on the museum’s website, “[His story] lets people know that brilliance can be found anywhere, even a small Southern town.”